December 2025 Newsletter

Join us for a January-April 2026 exploration of Virginia Woolf’s “Mrs. Dalloway.”

Consequential works of art pass the test of time and meet us throughout our lives. “Mrs. Dalloway” is now celebrating the 100th anniversary of its publication. Great books warrant reading and rereading. Maybe you’ve read this book or maybe it’s on that list of books “I’ve been meaning to read.”

Not everyone has read Virginia Woolf, known for her “stream of consciousness” writing style. But here’s the thing: if you know the text may switch mid-paragraph from one character’s thoughts to another’s (but never more than one switch), and from the present back to their adolescence (but to no other time), you’re ready to read Woolf.

She was unafraid of compound-complex sentences, but they seldom run more than ten lines. Compared with Henry James’s two-page, one-sentence interior monologues, Woolf is downhill sledding. And while she does pose unanswerable questions, she is not metaphysically obsessed like Melville. Woolf’s novel is not trying to explain the universe but to reflect how our minds actually work. Put another way, she’s not a Victorian, she’s a Modernist, and we should be grateful.

We read Woolf for several reasons. First, we read her for what she wrote, including great novels. One way to recognize a great novel is to see if later writers responded to it with good or even great works of their own. This respect can set off literary “chain” reactions: “Don Quixote” responded to centuries of chivalric romances, and Flaubert responded to Cervantes with “Madame Bovary.” Percival Everett’s “James,” a response to “Adventures of Huckleberry Finn,” won the 2024 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction. “Mrs. Dalloway” prompted Michael Cunningham’s “The Hours” (1998), which also garnered a Pulitzer Prize for Fiction and was adapted for film and opera; and Robin Lippincott’s “Mr. Dalloway” (1999).

Second, we read Woolf because of who she was. The figure she cut in London during the 1920s can only be compared to the central importance of Gertrude Stein among expats like Hemingway and Fitzgerald and Dali and Picasso in the Paris of the same 1920s.

Third, we read Woolf because she is, in a word, delightful. Take a look at her essay “How Should One Read a Book?” There, you will fall in love with Woolf’s written “voice,” her level-headedness and generosity toward readers and writers, and her strong reminder of why we read in the first place!

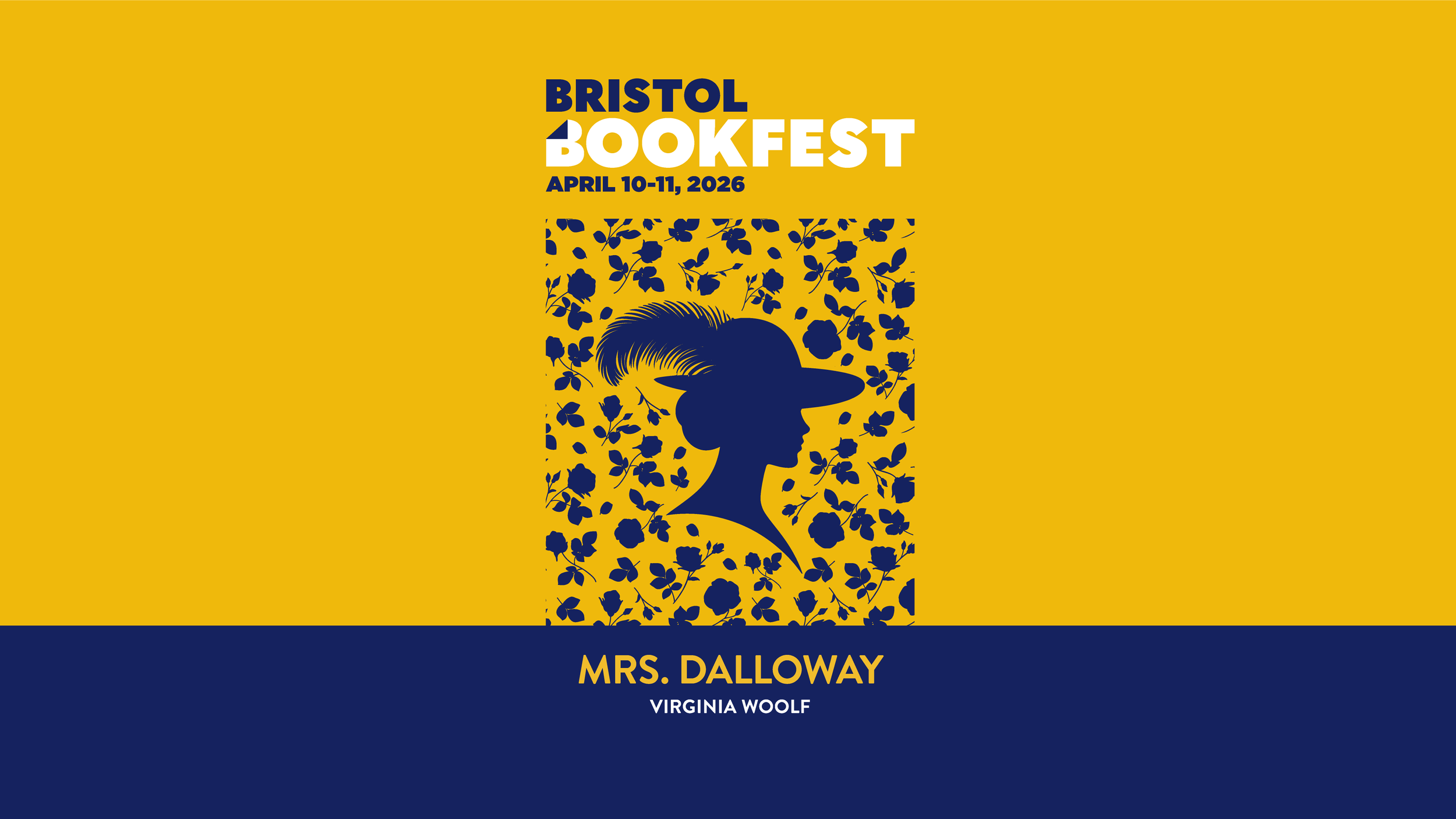

Our annual, weekly Winter Seminar (Tuesdays, 6-7:30 p.m., Jan. 20 through Feb. 24, 2026) at the Rogers Free Library will explore these three aspects of Woolf and take a close look at key portions of the text—before concluding with a special “Bloomsbury Salon” on Feb. 24. We’ll send an announcement when registration opens. The exploration will culminate in a weekend of lectures, discussions, and community engagement on April 10-11, 2026. Hold the dates!

If you don’t have a copy of “Mrs. Dalloway” on your shelf, check out one of the five copies donated by the Bristol BookFest Committee to the Rogers Free Library; Ink Fish Books in Warren, RI, offers a 10% discount on the paperback to anyone who mentions Bristol BookFest. Enjoy the book!